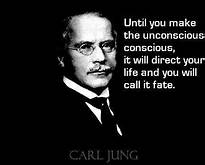

Carl Jung (1875-1961; pronounced “Yoong”) was a psychologist who worked when modern psychology was an emerging science. He studied under Freud, who found patients’ psychological problems often resulted from experiences earlier in life that were repressed into the subconscious. Jung noticed that some patients’ subconsciouses seemed to contain items that were not directly related to their lives. He set about trying to discover what other psychic contents might be in the subconscious.

What he learned in his research led him to label parts of the subconscious that did not come from an individuals’ direct life experiences. They were part of what he deemed the universal unconscious (i.e., they were not individual and they were not the subconscious that Freud was studying, which was based on personal lived experience). These included reoccurring stories, images, emotions, and patterns, which he called archetypes. And there was a part of the subconscious that seemed to consist of everything that the individual when in society was not: this he labeled the shadow.

He and others who followed him continued to explore these aspects of the mind and found how they went a long way toward explaining human behavior in ways that other explanations did not. As Joseph Campbell, one of Jung’s followers, once said, “an economic theory of human history could never explain a Chartres (Cathedral)  . Meaning: there is something else at work in humans than mere day-to-day concerns. Some universal unconscious aspect (I’ll call it here “a need for spirituality”) drove many people in Chartres for hundreds of years to come together to build a place of worship more magnificent than any business or home.

. Meaning: there is something else at work in humans than mere day-to-day concerns. Some universal unconscious aspect (I’ll call it here “a need for spirituality”) drove many people in Chartres for hundreds of years to come together to build a place of worship more magnificent than any business or home.

So then, what is in this universal unconscious that we all have inside of us? And how can it help us understand our own behavior and that of other humans? Let’s begin with two of the most important concepts/aspects: archetypes and the shadow. Understanding these two concepts is important to understanding the overall view of how the universal unconscious affects human experiences and behaviors.

Archetypes are collective; “the effects they produce” are individual (according to Jung). So how can we show that they exist and what they are?

Archetypes are collective; “the effects they produce” are individual (according to Jung). So how can we show that they exist and what they are? The chicks stopped peeping. The archetype of that predator bird’s shadow was inside each chick at birth, and it set off the behavior of being quiet so as not to be discovered and preyed upon. This image had been passed down because it was important for the animal to survive that the image be in the animals’ brain/mind to touch off the proper behavior when the experience arose. This to me is one of the best examples of both how archetypes act and proof that they exist.

The chicks stopped peeping. The archetype of that predator bird’s shadow was inside each chick at birth, and it set off the behavior of being quiet so as not to be discovered and preyed upon. This image had been passed down because it was important for the animal to survive that the image be in the animals’ brain/mind to touch off the proper behavior when the experience arose. This to me is one of the best examples of both how archetypes act and proof that they exist.

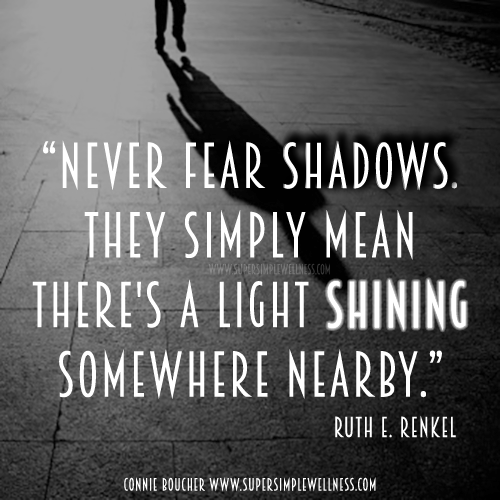

But Jung’s own definition went on to clarify, “If it has been believed hitherto that the human shadow was the source of evil, it can now be ascertained on closer investigation that … shadow does not consist only of morally reprehensible tendencies, but also displays a number of good qualities ” [CW9 paras 422 & 423].1 One of his most famous students, Maria Louise von Franz, cited a woman Jungian therapist who worked with some of the hardest criminals in jail and found that their shadows were incredibly positive.

But Jung’s own definition went on to clarify, “If it has been believed hitherto that the human shadow was the source of evil, it can now be ascertained on closer investigation that … shadow does not consist only of morally reprehensible tendencies, but also displays a number of good qualities ” [CW9 paras 422 & 423].1 One of his most famous students, Maria Louise von Franz, cited a woman Jungian therapist who worked with some of the hardest criminals in jail and found that their shadows were incredibly positive.

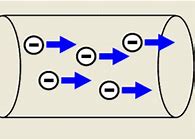

or a negatively charged particle in physics

or a negatively charged particle in physics  . Negative for him was a scientific term and not a judgment. It was negative in that it was not lived out or processed. It would be no truer with these words to say that everything one actually did in real life was positive in the sense of good. It is merely positive in the sense of being manifest like the positive image of a photographic negative: it has been brought to light.

. Negative for him was a scientific term and not a judgment. It was negative in that it was not lived out or processed. It would be no truer with these words to say that everything one actually did in real life was positive in the sense of good. It is merely positive in the sense of being manifest like the positive image of a photographic negative: it has been brought to light.